This is an image of an ‘explosion near the Pentagon’ that (never) happened on May 22nd 2023.

To the left is a large column of smoke rising up, as if from behind trees or bushes. A building that simultaneously resembles an office-block and a neoclassical grand facade is partially visible in the background. There is metal fencing dividing the image horizontally, which resembles the temporary modular barriers commonly seen at concert venues or around construction work. However, the barriers in the picture are full of inconsistencies: warping, fuzziness, escher-like bends and overlaps. In the foreground I see a curved pavement and patches of grass, inexplicably growing out of the stone surface. When I zoom in I see more blobsters1: a lamp-post, the top part of which looks ‘smudged’, as if swaying, and windows of the building in the back which hypnotically blend with the wall forming irregular shapes. It is clear that the building is not the Pentagon.

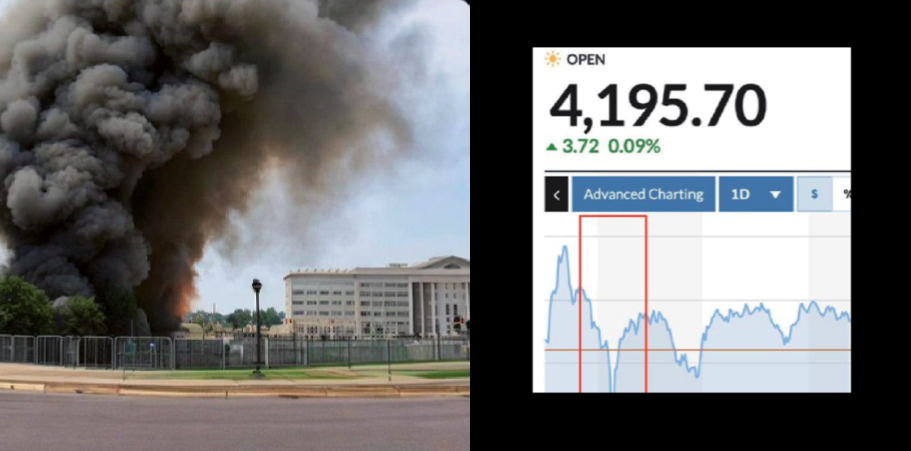

Is it possible that this image could fool anyone as a photo of a real explosion at the Pentagon? By all appearances the answer is: yes! Tracking interactions of Twitter users (with the number of views of a singular re-share exceeding 100 000) it is apparent that the image of the explosion at the Pentagon was a successful, albeit short-lived, hoax. Mainstream media quickly raised alarm about the ‘terrifying’, ‘worrying’ or ‘scary’ potential of AI to bring an end to the era of visual truth, manifested in the capacity of this fake to fool hundreds of thousands of viewers. Beyond its social media popularity, the publication of the fake coincided with a drop in S&P 500 (an index expressing the confidence, or faith in the market) and the cryptocurrency Ethereum, among others.

In the case of most visual hoaxes, the image is usually abandoned once it’s either confirmed or debunked. Following Jean Baudrillard’s proposition to to ‘attend to the question of proving the real through the imaginary, (…) the proof of art through anti-art’2, in my ongoing art and research project: Anatomy of Non-Fact I attempt a search for the visual aesthetic of fact through the analysis of hoaxes.

The problem of mass mis-information or even deliberate and targeted dis-information isn’t a problem of technology finally mastering visual media mimicry, despite the mainstream media narratives. While the anxiety about the crisis visual truth is warranted, the root of it is arguably misidentified. Current discourse over-prioritises the role of visual technology while dismissing the impact of the pace of perceptual processing, which the information is demanding. Arguably this ‘picnoleptic’3 processing conditions the reading of visual media more than the image itself. The problem of speed is inseparably a problem of volume, and ultimately asks us to view each disinformation image in the context of many others, as part of a montage of sorts, or a layered system of narrations, symbols, associations and meanings. In this analysis, the image is not restricted to its boundary, but extends beyond: to a network of connections, associations, and the more tangible networks of copies, crops, re-shares, comments and likes.

The necessity of stepping beyond the boundary of the image means also looking at the immediate framing: at symbols and at words that sit next to the image. On social media posts the image will often be attached to a longer caption, which has an appearance of a description, but actually contains an instruction for the viewer. ‘Explosion at the Pentagon’ means ‘check if the image contains an explosion and the Pentagon’. The image is there to corroborate the written statement, relying on a long post-photographic tradition of journalistic visual trust-building. Once the viewer follows the instruction and is satisfied that the image and description match, they are likely to move to the next task4. The image-text pairing therefore aestheticizes the viewer5 to a particular task-oriented way of seeing.

Both these aspects of the synthetic hoax image: its networked position, and its instructional function, are key for its analysis.

1. Memories

The image activates a network of memories, conjuring and forming associations. These will differ from person to person, yet overlap around common experiences, and collective cultural, visual and media contexts.

When I see the image of the supposed explosion at the Pentagon, my attention is immediately consumed by how strangely dense and massive the smoke appears, despite seemingly coming from some bushes or trees. The indexical function of smoke automatically makes me think of explosions in films. For a short moment I recollect how similarly abstract and otherworldly they look. My mind starts to recall images of real explosions I saw, and immediately questions whether I remember seeing any images of the Pentagon explosion during 9/11. I was 10. I remember returning home from school at around 14.00 o’clock. My dad was home too, which was odd at this time of day, the tv was on and he was practically glued to the screen. My mum made a new recipe for obiad (mid-afternoon meal), which I disliked (rice with lemon-chicken sauce), but what about the broadcasted images of the event? The ‘twin towers’ catching fire override much of my visual memories. I know the Pentagon was attacked on the same day, but I can’t picture it. Have I ever seen it?

Is it possible that I saw the Pentagon explosion back then and the visual memory got simply overwritten by the picture of twin towers?

A quick online search reveals that high quality photographic documentation of the immediate aftermath wasn’t released until 20136. I didn’t see the explosion at the Pentagon back in 2001, none of us did. The only visual memory of the real Pentagon explosion is expressed through a stand-in: a symbol of another location, another explosion.

The smoke in the fake image is as thick and dark as the one coming from the World Trade Centre. As Forensic Architecture’s Cloud Studies put it ‘the (…) cloud contains everything that (…) once was’. The dense, black smoke in the fake image is typical of burning rubber, trash, vehicles or buildings, which doesn’t make sense since the smoke emerging from trees and bushes, which are known to disintegrate into white-gray clouds, resembling more a thick vapour than a heavy opaque plume.

The resemblance of the fake explosion to the plume coming off the twin towers on 9/11 is apparent. The now iconic image imbricates the fake with real memories and affect. The operational function of the fake, the instruction for the viewer to act and feel a certain way (panicked, terrified, shocked), is in a way embedded in the now symbolic quality of the smoke.

2. Surveillance Aesthetic

While searching through the visual archives of the 9/11 Pentagon explosion aftermath, I found that following a 2004 FOIA request two clips from two CCTV cameras outside of the Pentagon, were also shared.

When I look at the real 2001 explosion CCTV image, the distortion of the visual plane characteristic of a wide camera lens is immediately apparent in the shape of the sidewalk. The same feature is present in the sidewalk of the fake image. Contrary to the real image however, in the fake, the wide-angle distortion doesn’t spread to other parts of the image. In fact, the capture of the building in the back approaches an orthogonality characteristic of a standard/longer focal length.

Could the CCTV-lensing of the fake sidewalk be signalling something? It possibly speaks to the influence of the CCTV portrayal of the real Pentagon explosion in the dataset, that is: if the fake had been indeed AI generated. Nevertheless, whether it came from photoshopping, an algorithmic choice, or a hybrid of the two, it was ultimately up to a human to select this image as the one that best depicts an explosion at the Pentagon. It was a human decision to share, re-share, and to comment on it.

I continue to perform an archeology7 of the image and aim to extract more layers of information from the image. I begin to question if it could be possible that for the author and at least some of the audiences, the echo of the CCTV sidewalk triggered an association with the prior, real explosion at the Pentagon. CCTV imagery appeared in commercial use and in visual culture around the time of 9/11. The surveillance aesthetic it brought about found its reflection in films like Timecode, the rise of popularity of reality shows like Big-Brother, and series like CSI8, and The Wire.

One could go even further, and view the fake Pentagon image in an almost linear genealogy of surveillance aesthetic unfolding backwards in time from the CCTV fish-eye lensing of the sidewalk to the perpendicularity of ‘aligning ocular perception along an imaginary axis’9as inscribed in the frontal portrayal of the faux Pentagon, echoing the orthogonality of forensic convention originating all the way back in forensic photography of Alphonse Bertillon. Now, 20 years later with the surveillance aesthetic fixed in visual culture, it communicates a sense of transparency and objectivity.

However, visibility can be a tool of deception itself.

The same CCTV pictures of the real explosion at the Pentagon were used to support conspiracy theories in the early 2000s. The lack of legibility of the very low frame rate of the CCTV video and the low resolution paired with dramatic effect of the wide angle lens warping the visual plane, likely reinforced the already existing belief of conspiracists: that the US government was trying to obscure the truth because of their supposed involvement in the attacks..

Access to something otherwise hidden, creates an illusion of access to higher knowledge, reinforcing the panic in the conspiratorial mind. A CIA Deception manual frames this idea under ‘Magruder’s principle’10 while Adorno calls this a ‘mediation between the world and the individual psyche’. He continues by stating that ‘the agitator molds already existing prejudices and tendencies into overt doctrines and ultimately into overt action11.’ This mechanism, of claiming visual records as fake, in the post-Trump era is termed as ‘a liar’s dividend’. The lie works because it bears resemblance to an already preconceived expectation of reality in the conspiratorial mind. Most recently, another function of the liar’s dividend became clear, through Trump’s bold and absurd statements during his presidential campaign of 2024, visually preserved by the AI-generated poster of Taylor Swift’s supposed Trump-endorsement. The relationship of Trump’s claims to reality became irrelevant. Perhaps the act of lying in an obvious way is becoming to a conspiratorial mind, which distrusts everything, a liberating gesture. The boldness and absuridity of an obvious lie is becoming a manifestation of power, unaffected by debunking and fact-checking.

3. Hyper-event

The description with which the fake explosion image was originally affixed read: ‘An explosion near the Pentagon building’.

The ‘nearness’ is the key word here. It’s an explosion that nearly happened at the Pentagon depicted by an image that is almost convincing. It wouldn’t be much harder to visually fabricate the smoke coming from the Pentagon building directly (whether with AI or photoshop or a hybrid of the two) than an explosion near the Pentagon. Yet, an explosion originating directly at the Pentagon building could have drawn too much attention, would have been too unbelievable and possibly lead to an even faster debunking. This nearness is also manifested within the temporality of the portrayed event: rather than capturing the moment of the explosion, the image offers a view of the aftermath. There is also the physical distance between the explosion, coming from behind the bushes on the left, and its unknown origin. We don’t know what exactly caught on fire. The near-distant lapses of the image, the blurring and the ‘almost’ of the explosion offer an opportunity for the conspiratorial mind to edit the imagination of the event based on their preconceived narratives. Echoing Virilio’s idea of the picnoleptic state, which expresses the tendency of individuals to create an impression of continuous time, without any apparent breaks, in a way ‘editing’ out interruptions. Seeing the aftermath of an explosion without an origin, the conspiratorial mind takes on this vagueness to fill the space in-between the explosion and the imagined state before.

‘Carefully design planned placement of deceptive material’, instructs CIA’s deception manual, referring to the way that deception material should be placed to best deceive a ‘target’, i.e. in such a way that the receiver has to put some effort into discovering it, or interpreting it. This sense of accessing ‘privileged’ information is playing out already in the social media dynamic. The fake explosion image was seen largely by followers of the mostly right-wing, crypto, and bro-OSINT accounts: audiences which already have a sense of being part of a uniquely enlightened group. However, this maxim also plays in the nearly good visual quality of the image. The viewer has an impression that they are looking at something not entirely obvious, something requiring effort to fully understand. The image appears imperfect, yet complex, exemplified by the hallucinatory dance of windows outside of straight lines and rules of perspective, or the delirious bending and overlapping of metal barriers. Such complex representation induces a state of visual overload. Since the mind has a limit when it comes to processing complex visuals, in a similar manner to that with which camouflage convinces us about continuity of a background, the complexity of errors in the fake Pentagon explosion image, can convince the mind of its accuracy.

This near-distant quality characteristic in general of images of disasters, led me to define a category of ‘hyper-events’12, i.e. images of events, which the privileged audiences consisting of distant witnesses primarily experience as representations, at a geographical and temporal distance. The seeming urgency of a hyper-event is paired with the incomprehensibility of real scale as well as sensorial unrelatability of the portrayed scene. Contrary to a lived experience, an image of an explosion or a smoke-cloud is viewed without any connection to the body of the distant witness, who has no way to understand the feeling of inhaling the dense air and coughing it up, who won’t know the sound of an explosion, the way its kinetics push and resonate in the body, the way that the cloud hurts the eyes and obscures the vision… among a range of other indescribable sensations and feelings that I myself, as a distant viewer, can only learn about from accounts of others. Even though the events portrayed in hyper-event images are real, the near-distant, uncanny quality alienates the event from the viewer, arguably also priming them to in turn not question the even more uncanny qualities of the fakes.

When discussing the individual experiences of viewing images of disasters, graphic and violent imagery or portrayals of destruction, with fellow researchers, artists and filmmakers, I noticed that while individual sensitivity and experience vary, the prevailing ideas are somewhat limiting. Many of our conversations ended with some way of expressing the belief that the images of violence desensitise us, or to the contrary: that they traumatise us as audiences. I believe the issue is much more complex, and hinges on the instructional (or in some way even operational) relationship of these visuals to perception. Images, especially news images condition and ‘modulate’ perception13. Their effect on individual action is not 1:1, not linear and direct, but rather operates on repetition, reinforcement and feedback.

4. Panic image

Explosions of US governmental buildings have become an established trope in the mainstream disaster film genre and expressed a certain type of ‘lingering anxiety of the time’14. The 1996 film Independence day produced imagery of the White House under attack. The 2013 White House down is one of many other films continuing to add to build on this imagery and to the practice of compression of storytelling to a series of ‘explosive events’15.

The present state of lingering anxiety is a product of modern warfare, transferring the space of the battle, to the space of constant waiting. This sense is produced at least partly through imagery of ‘hyper-events’, of atrocities, wars and catastrophes. Paired with lack of action and a felt material effect, these images further contribute to a state of suspension: ‘always on low–boil poised for action’16. Displaced warfare occupies so many aspects of our life, albeit to varying degrees, even if we are far away from the battlefield. A disaster returning to the site of historically centralised military operation, like the Pentagon, is not only a symbolic release of an anxiety or anticipation of a consequence of the prolonged ‘soft power of the nonbattle’17, as Brian Massumi frames it, but also a way of reifying the immaterial fear, making the invisible somewhat more tangible, effectively reaffirming the lingering unease.

While near-event or hyper-event is aligned with a precarious condition of sensing an ever-impending disaster, a looming threat modulating our perception, the image of the fake explosion at the Pentagon becomes a ‘panic image’. As such it releases the tension of the nonbattle and relocates it from the invisible sphere of the epistemic, environmental or cyberwarfare, into the old convention of theatre of war. This way the symbols finally reaffirm and underline visibly that, which is already felt. The panic image has therefore a potential to at least briefly affect the audience, and confirm their pre-existing beliefs developed in the space of ‘endless waiting’.

5. High-frequency images

When revisiting the spread of the misinformation around the fake Pentagon Image, I can see that the correlation between the publication by crypto-accounts (as well as a particularly suspicious account posing as Bloomberg’s official channel) correlated directly with the drop of S&P 500 and of some cryptocoins like Ethereum. The drop continued for around 4 minutes after the first crypto-accounts posted, recovering quickly after that. The image went viral in some Twitter communities, but nobody I know who is outside of the OSINt community seems to have seen it. Algorithmic trading is one of the possible explanations for the image’s ultimate effect on the market. A known attack of similar magnitude and duration in stock-fall occurred 10 years ago. It was caused by a fake Associated Press post on Twitter claiming: ‘Breaking: Two Explosions in the White House and Barack Obama is injured’. Contrary to the faux Pentagon explosion, this post didn’t have an image attached to it.

10 years ago the algorithmic analysis of news was said to be fairly simple, and in the early stages of customisation: an algorithm would search for particular word or phrase combination from reputable news sources. The companies and systems behind algorithmic trading are opaque and one has to rely on informed speculation to understand whether and how an image can feed into high-frequency system. The hack attack exposed vulnerabilities of these systems, and demanded improvement in validation, verification and analysis of the news claims. It is probable that in the case of the Pentagon, machine vision analysis of the image serves as another level of verification of the written claim. Rather than performed by one of the software companies, it is most likely that the ‘explosion near the Pentagon’ was an attack organised or partly scheduled by crypto-traders in order to test the possibility of shorting the value of certain cryptocurrencies, like Ethereum, with visual news-aesthetics. Some accounts could have been in on the conspiracy, others seem to have been genuinely convinced by the posts, and spread the misinformation in panic, causing a chain reaction. Just as the 2010’s algorithmic trading system, ‘drew on affective contagions of networked social activity as well as financial data’18, in the ‘Pentagon explosion’ case the visual aesthetic of the disaster image could be serving a similar purpose. Since images slowly formulate our idea of a future to come, of reality that is ‘slowly and imperceptibly brewing’ they also modulate and train our attention19 through repetition, visual qualities and contextual instructions, often resulting in anticipatory actions that affect the immediate dimension of time, rather than future.

After the Pentagon explosion post was shared by multiple crypto-accounts, it took less than 10 minutes for stocks to drop and recover. In the span of a day, this event had virtually no effect on the market. The fake event wouldn’t have been probably even reported by the media if it weren’t for the market crash, and for the role of the market in neoliberal media and politics as the ultimate measure of truth. The tracing of direct consequences on the material realities between events and market values is nearly impossible, among the temporal complexity of output. The repeated ’micro-crisis events’20 however, have historically had an influence on entire large scale crises.

The essence of the post-truth era becomes clearly manifested here: a social media space, which just a few years ago had an instrumental function in news production and sharing, is now turning into a market manipulation platform. The manipulation is banal, the political message becomes utilitarian rather than stemming from conviction. The malice is at its root self-serving rather than ideological. I can’t think of a better way to exemplify the fallacy of persisting techno solutionist narratives than with this example, so clearly pointing at the affective capitalist21 manipulation via a corrupted aesthetic of fact.

6. Deep realities

The verification of suspected synthetic hoaxes is dependent on access to api’s of services, operating between software updates and policy changes. Many tools and techniques for verification of images become outdated very quickly, affecting the changes in the landscape of misinformation, but also of its investigation.

One of the more accessible tools for image verification is reverse image searching. The reverse search results for the sources of the Pentagon explosion image, indeed identify it as the Pentagon. In this case the volume of articles reporting on the fake Pentagon led google lens’ results to confuse it with the real location. Distinction between fake and real gets even more fuzzy when next to google’s results a location tag for the Pentagon appears with a 4 star rating and a comment on the availability of parking space. We have entered deep reality.

Deep realities contrary to deep fakes are not singular images or videos, but consist of entire multimedia narratives. The ability to form stories or narratives is what distinguishes misinformation from deception. Deep realities are self-referential, symbolic and reinforced by existing technological networks.

In 2023 a group of redditors generated a faux ‘photo-documentation’ or are reportage of the ‘2001 Great Cascadia Earthquake and Tsunami’ event. With over a 100 of images, an entire story developed around one retro-speculative scenario. Similarly to the fake Pentagon explosion, this story too tapped into existing anxieties and a probable reality. Cascadia subduction zone has been historically a site of mass earthquake events. In the last 10000+ years, 80% of the time the fault erupted before 324 years passed. Since the last earthquake occurred in 1700, given this statistical interval, an earthquake in the location is now ‘overdue’. The fake takes place in 2001, around the time of 9/11 and the real Pentagon explosion. It may be a coincidence, but perhaps it hints further at the weight that this moment in recent western visual culture has had on the collective imagination of western disasters and catastrophes.

The images of the event manifest typical tropes of disaster photography for an event like this: damaged overpasses and bridges, governmental buildings turned into rubble, recovery and rescue events. White men in suits looking serious in front of the sites of damage, or shaking hands with firefighters and affected civilians. There are so many images, one corroborating the other, that they begin to form entire narratives. Especially to someone unfamiliar with Cascadia subduction zone area, they have an appearance of truth. Since the faux event occurred 23 years ago, the images have little to no consequence. The ‘Great Cascadia Event’ images weren’t created to disinform, rather to play out a possibility of a catastrophic event. The images weren’t consequential to financial and political realities, but they show a heightened awareness of aesthetics of western disaster photo-journalism. Similarly, even though The fake Pentagon explosion managed to briefly stir the stocks, and confuse some audiences (already prone to accepting and spreading misinformation), the image is in its essence a declaration of a new relationship to documentary aesthetic: a photorealistic return to the pre-photographic use of visual metaphors to produce knowledge visually.

7. Inconsequential image

The reality proposed by the fake Pentagon explosion hoax speaks to a new event, one that is otherwise unrecorded. While it hinges on real lingering anxieties, it doesn’t directly tie in to any specific known events. Hoaxes that tie in to current and known events, blur the boundary between fake and real further.

In late 2023, an Adobe Stock AI-generated image of an explosion was used to accompany many stories around Israel’s attack on Gaza or as the caption next to Adobe Stock image puts it ‘conflict between Israel and Palestine.’ Despite the overwhelming amount of photographic visual documentation of the destruction and suffering in Gaza, the AI image was shared by multiple media outlets. Beyond the obvious and distasteful monetary motivation by Adobe to publish this AI-generated image, the use of the image in reporting points at the comforting de-realisation that images like this provide. Instead of showing graphic, unbearably heartbreaking images and recordings of personal injuries, stories and suffering, the image of a sourceless explosion signals a return to the symbolic representation of conflict. The image offers a familiar aesthetic of the western media portrayal of disasters as a way of neutralising reality. The AI-generated explosion, like other AI-generated war images, serves a purpose beyond information: it participates in constructing media narratives that passively describe the visual evidence with neutral language, as part of a performative and protective impartiality. These qualities now embedded in the fake explosion image, overshadow the affective potential of other visual records, turning the events into hyper-events. This is a continuation of the western media’s denial about the reality portrayed by visual evidence of atrocities, in which they are, at least passively, implicated. Simultaneously on the side of audiences, the abstractions offered by the AI image also serve a role of a protective mechanism around the inconsequentiality of images coming from Gaza. The ‘All eyes of Rafah’ image, reshared over 47 million times on instagram in May of 2024 is an abstracted top down perspective overlooking a vast landscape with rows of tents. The immense popularity of the image happened not in spite of its artificiality, but because of it. Reality is being denied, fakes are used for reporting and images considered too graphic are persistently censored on social media platforms. In this context an image that is very clearly fake can act as a tool for expression and simultaneous rejection of the seemingly inconsequential role of image in the mainstream media narratives.

The proof of fact through non-fact

The conspiratorial mind is one that is prone to be convinced by hoaxes and manipulations. While the majority of the more obviously manipulative, conspiratorial visuals oscillate around right wing groups online, the uncomfortable truth is that we are all prone to naive realism, a conviction that individually we are better equipped to discern real from fake than other people. Successful disinformation happens in less obvious ways, for example through repetitions of banal imagery or sanitised language, and is rarely a direct and bold ‘attack’. Unfortunately with the acceleration of the ever evolving absurdities of visual misinformation, the speed with which we accept the less obvious biases and manipulations of images also increases. What seems unacceptable or unimaginable today, may not be this way tomorrow.

The media landscape is at times described like another battle space, but in reality it’s more a training field, slowly and steadily conditioning our perception. We are aestheticised by images and instructed by images. Their repetitions form perceptual and emotional habits, conditioning our attention. It’s normal, and self-protective in the short term to push the problem away, or block it out of fear or confusion, but it can’t be a fixed state. We still have time: to reclaim our space with our own images and to critique and question simply how different images make us feel, if at all. Looking closely at news images through categories of hyper-events, panic images, inconsequential images and deep realities is one of the ways towards reclaiming agency over our individual perception.

In the times of increased inconsequentiality of the image, where governments close eyes to the visual records coming from Gaza, where images of other atrocities aren’t given their place, when the truth is called a fabrication and the fabrication truth, we need to look at the images as signals of non-visual, virtual or unlocatable truths and phenomena. We need to go beyond the fast-paced and task-oriented way of seeing and instead learn to read the images over and over again.

Martyna Marciniak is a Polish, Berlin-based artist and researcher. Her work explores spatial storytelling, speculative fictions, and 3D reconstruction to investigate cases of systemic violence and human rights abuses and question the role of technology in perpetuating or undoing existing biases and misconceptions. She has worked with media outlets including CNN and BBC, as well as NGO’s including Forensic Architecture, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch. The research group Border Emergency Collective, which she co-established, investigated and documented stories of migrating people at the Polish-Belarusian border. Her artworks were exhibited at the Biennale Warszawa, Kinema Icon in Bucharest, Haus Gropius in Dessau, and deTour Festival in Hong Kong, among others.