Another common characteristic among the series of characteristics, that Star Susan Leigh gives us, in The Ethnography of Infrastructure is that infrastructure becomes visible upon breakdown: ‘the invisibility of infrastructure fades away when it breaks’.1

In an era marked by an ongoing genocide, wars, climate crisis and migration, rising authoritarianism, and the resurgence of right-wing populism, and pandemics, infrastructures are getting more and more visible, for the simple reason, that they are getting more and more broken.

This is evident in digital spaces as well and many scholars from various fields have pointed out the necessity of rethinking (digital) infrastructures. The term enshittification, a term coined by Cory Doctorow, describes the gradual decline of digital platforms as they shift from prioritizing user value to maximizing profit extraction. This process is deeply tied to digital infrastructure, particularly its centralization under large corporations. Such control enables monopolistic practices like locking users into ecosystems, over-monetizing services, and manipulating algorithms to favor paid content. As platforms prioritize profit, they erode the quality of public digital goods, diverting resources away from open-source or decentralized alternatives. The environmental impact of enshittified platforms is also significant, as their data-intensive operations drive unsustainable growth in infrastructure. Furthermore, society becomes increasingly dependent on these profit-driven systems for essential services, undermining accessibility and resilience. Addressing enshittification requires rethinking digital infrastructure to prioritize decentralization, public investment, and fair governance that serves users and the common good over corporate interests.

Mel Hogan’s work, particularly on the politics of data centers and infrastructure,2 helps contextualize how digital spaces are often governed by monopolies of surveillance, exclusion, and extraction. Hogan’s research highlights the necessity of rethinking digital infrastructures and their materialities through a feminist, anti-colonial lens, urging us to consider who controls these systems and who benefits from them, focusing among other things also to the enormous footprint and consumption AI digital infrastructures demand in order to function.

It’s inevitable that the collective imagination gets then fixated on apocalyptic visions of collapse, with this pessimism limiting our sense of agency. Could one instead adapt in the face of collapse or catastrophe? Is it possible to co-design with catastrophe itself?3Is it possible to rethink of infrastructures and to think of alternative infrastructures?

It seems that now, more than ever, we need new infrastructures that enable us to imagine alternative futures—ones that are resilient, equitable, and grounded in relational ethics. At this critical juncture, the future cannot be seen as a fixed destination but as a multiplicity of interconnected pathways, shaped by systems that prioritize interdependence, ecological responsibility, and inclusivity. Possible futures, where humans, machines, plants, and animals, human and non-human beings coexist in a non-anthropocentric understanding of the world. Is this even possible?

In my artistic and research practice,4this kind of inquiries have consistently emerged in the form of multimedia installations with infrastructure being consistently a focal point—a space or an idea to be reclaimed or reimagined for collective storytelling, trust-building, and fostering relationality. I suspect this inclination to poetically rethink and reinvent infrastructures is rooted in my experience of being born, raised, educated, and entering the job market, in the European periphery, in Greece, in a country profoundly impacted by economic crisis at the time, marked by collapsing systems and infrastructures and still struggling with its lasting effects.

These multimedia installations seek to reimagine or reinvent the infrastructure beyond mere connectivity or function, seeing it instead as a shared ecosystem where local narratives and planetary systems and intelligences coalesce into an interconnected, resilient whole.

In the following paragraphs I will briefly go into some of these installations that reimagine infrastructures that could either be described as counter infrastructures that set the user in the center (Dragona 2014)5or as affective infrastructures, infrastructures that are able to accommodate multiplicity and resistance (Berlant 2016).6

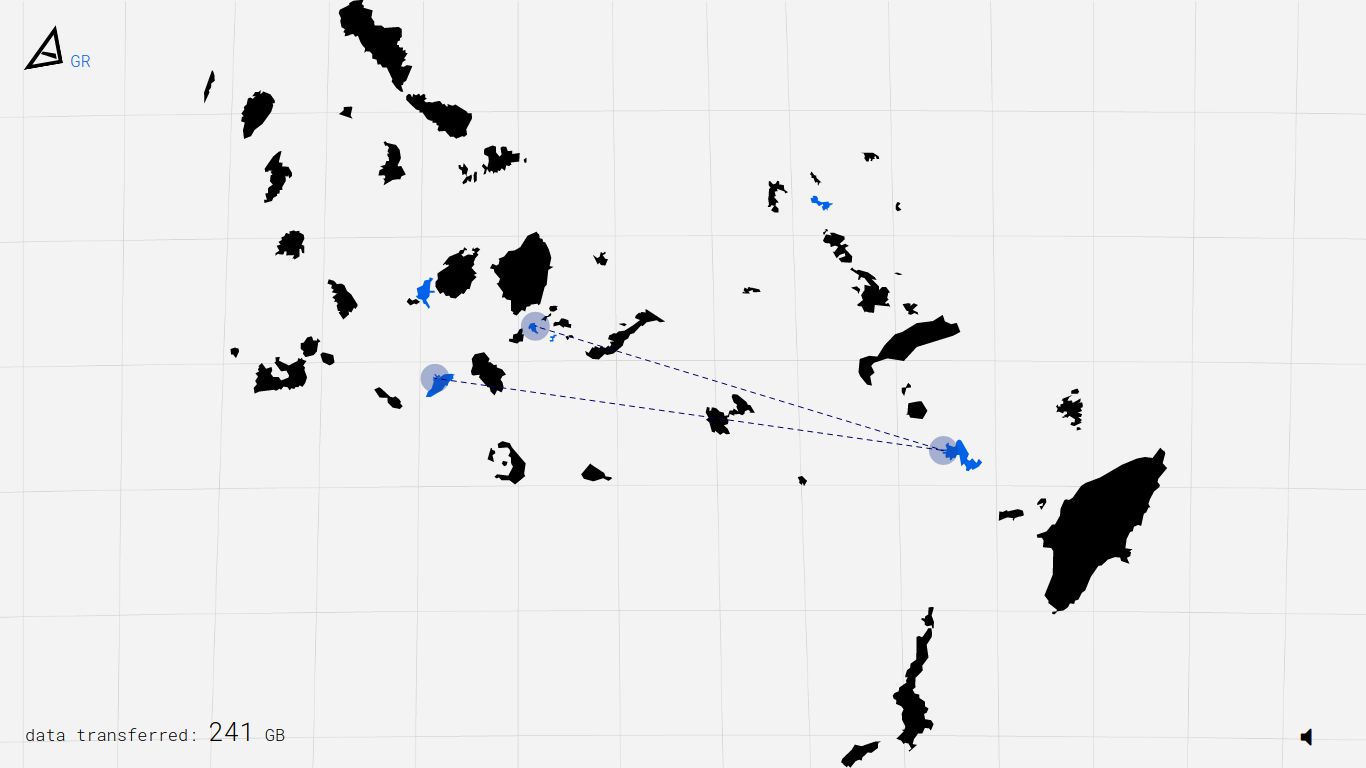

Image: The Aegean Datahaven A cooperative platform in the Archipelago. Website screenshot 2017 ©Kyriaki Goni

The Aegean Datahaven A cooperative platform in the Archipelago, a project launched in 2017, provides a significant counterpoint to the corporate-led digital infrastructures that dominate our world today. The work is actually this cooperative platform that introduces themselves through their website, an anti-manifesto and a series of drawings attributed to a traveller of the period. Set in 2082, the imaginary cooperative platform is formed by the alliance of some islands of the Aegean Archipelago that joined forces in resistance to the exploitation of personal data and the corporate ownership of the commons and the Cloud. This vision confronts the centralized nature of digital sovereignty, which is dominated by tech giants seeking to profit from the personal and collective data of users around the globe. In the Aegean Datahaven, islands form a cooperative network, each connected to one another and to the broader world, asserting a new form of sovereignty—one rooted in collective action, cooperation, and community resilience.

The Aegean islands, long interconnected by myth, culture, and shared history, face social and economic pressures that can only be addressed through solidarity and mutual support. In this speculative future, the Aegean Datahaven offers an alternative to the exploitative systems that seek to commodify data and extract value from personal and collective information. The project challenges dominant notions of identity, geography, and power by creating new topologies and networks that decentralize control and assert the sovereignty of the collective over the corporate agenda. By re-imagining the Mediterranean region as a cooperative, digital platform, the Aegean Datahaven envisions a world in which infrastructure is not a tool of domination but a mechanism for collective empowerment and resistance against corporate colonialism in the digital age.

In the Challenging Infrastructures. Alternative Networking & the Role of Art, Daphne Dragona describes artistic practices that have constituted forms of ‘counter-infrastructures’ 7 and bottom-up initiatives. Offline sharing networks, tactical modes of connectivity, playful topologies have proposed counter-practices and modes of understanding that set the user in the center, regaining control not only of her data but also of information flows, connectivity, and infrastructures.

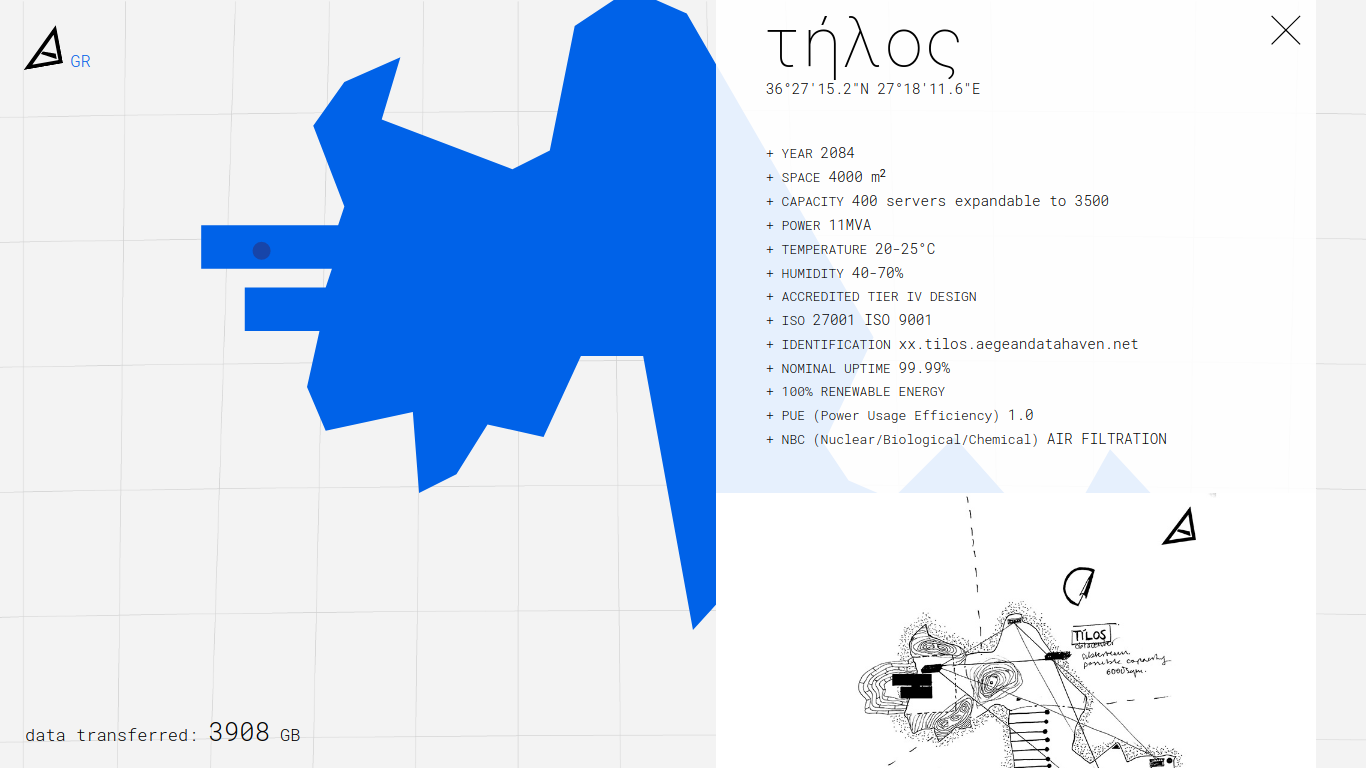

Image: The Aegean Datahaven A cooperative platform in the Archipelago. Website screenshot 2017 ©Kyriaki-Goni

She writes, [..] ‘the Aegean Datahaven (2017) comments on the current sovereignty of the Cloud, imagines a “decentralized network of small, fully sustainable, climate-controlled data centers.” A website and a series of drawings assist in telling the story of a new form of “local traditional platform cooperativism,” where the inhabitants of the small Aegean islands manage the data center, and users have the possibility to store and share digital information without relying on corporate clouds. Goni imagines a network where the topology of data centers and the topography of the islands meet, and the building of the new infrastructures assists the local economy, but also importantly respects the natural environment; she speculates upon the potential of new ecologies based on the co-existence of human and nonhuman elements, cultural and natural. The Aegean Datahaven, utopian as it might seem as a scenario, underlines how digital sovereignty and net neutrality can be achieved through the awareness and collaboration of the many, i.e. indigenous islanders, people who have abandoned urban living and former migrants’.8

Image: Launching the Node of the Networks of Trust on the island of Tilos 2018 ©Kyriaki Goni

The notion of network and the connectivity that insularity bears in it kept my attention and one year later I presented another multimedia installation Networks of Trust (2018).9 The installation acts as an allegory for the origins of networks in the Aegean archipelago and the Mediterranean Sea, weaving together past and future narratives of connectivity and coexistence.

The multimedia installation consists of the Poem of the Origin of Networks of Trust, an offline network of Nomadic Nodes, the Flag of the Networks of Trust and a Diagram of the Networks of Trust.

While hiking on one of the Aegean islands, I visited a cave where fossils of dwarf elephants were excavated. The paleontologist working in the area shared with me information about these findings. Researching further into this subject, led me to write the Poem of the Origin of Networks of Trust which was supposedly narrated by the convergence of fossil remains from a dwarf elephant and an artificial intelligence system. This is the starting point of the multimedia installation.

A crucial part of the installation is The Nomadic Nodes. The Nomadic Nodes are offline, combined with technologies such as P2P and the Interplanetary File System (IPFS) for distributed data storage resilient to potential censorship and control creating in this way a safe space for participation and sharing.

The Nomadic Nodes are activated in two different ways, the first one is through the audience’s participation while visiting the exhibition. The audience is invited to connect via their device to the Nomadic Node and type a short imaginary story on the possible futures in their region, mainly on the themes of climate crisis, migration and technology’s positive or negative implementations.

The second way the Nomadic Nodes are activated are through activation gathering. In these gathering, which I call activations, residents of the city are invited to participate to a community story-telling about the present future in their city. Introduced to the basics of storytelling, creative writing and worldbuilding they are invited to build and share their own stories. When the Nomadic Node in the 2nd Warsaw Biennale was activated, we discussed with the participants about their city in a local and global context. What will life in Warsaw be like in 20 or 50 years? What are the fears, desires and hopes for the possible futures? Is there a technology or an object crucial in this future? What will species migration and climate crisis look like in the future? What futures do they desire? The stories produced were written down and since then hosted in the Nomadic Nodes, alongside other stories from other persons from other places.

Through fiction and storytelling as a method of community building, the work invites participants to contribute their own stories of regeneration and amelioration, thus expanding the possibilities for a networked future. In doing so, it embodies the kind of infrastructural shift needed in our increasingly fractured and polarized world—one where networks are built on trust, cooperation, and shared responsibility, and where islands are not isolated but deeply connected to one another and to the global whole.

It is worth to note that no personal information is kept on the node. When a story gets uploaded, only the name of the city where the upload took place gets recorded. The stories shared on the node travel with the node and are part of the installation. Stories on the Networks of Trust nodes are accessible by proximity only and indexed as cryptographic hashes on the site archipelago2092.xyz

In Networks of Trust, this relational model is echoed through its decentralized nodes and community-driven narratives. By creating a space for local stories, these nodes encourage a bottom-up approach to infrastructure that honors community knowledge and memory. This method aligns with Indigenous practices of stewardship, where storytelling, ritual, and place-based knowledge are central to maintaining ecological balance. Such infrastructures do not impose control but cultivate reciprocity and respect for all beings.

This work has its origins in the deep-time networks and connections created in the Aegean Archipelago. The islands in the Aegean Archipelago have been formed under the influence of three major forces: tectonism, volcanism, and eustatism. The insularity and the archipelagic infrastructure carved the conditions for networks to arise. Islands may seem closed off from the world but are also spaces of movement and relationality. The island and insular existence combine isolation and connectivity, in ways through which we can rethink the past, present and future of networks. In Networks of Trust, the Aegean Sea part of the Mediterranean Sea is in the epicenter, embodying the tensions and potentialities of our interconnected world. From its ancient origins to the current social and economic dynamics, the sea and the network become a space through which to imagine new futures—ones grounded in mobility, climate solutions, and ecological regeneration.

In a sense every island is actually a fractal of broader networks that extend from small and local ones between two or more islands, to the entire Archipelago, and to ourselves, experienced and interconnected as bodies of water and nodes of Networks.

Networks of Trust poetically seek to offer a decentralized space for storytelling, memory, and trust, inviting community members to contribute without fear of surveillance. Here, infrastructure is returned to the people, prioritizing local narratives and allowing hyperlocal experiences to resonate globally. Networks of Trust is a nomadic work always in progress, adapting to different places and growing through the input and participation of different audiences.

Image: Networks of Trust, installation shot 2022 ©Kyriaki Goni. Solo show 68Art Institute Copenhagen. Photo by Jenny Sundby

Image: A Dense, Secret Network of Roots (Athens Data Garden), graphite on paper, 110 x 150 cm. Onassis Collection 2020 © Kyriaki Goni

To rethink or reimagine infrastructures that embrace multiplicity and resistance, and that are designed around interspecies communication: A Way of Resisting (Athens Data Garden) (2020)10 is a multimedia installation comprising videos, interviews, drawings, AR, and prints. It introduces a new type of infrastructure shared between humans and plants. The network centers on a plant endemic to the Acropolis hill, known to botanists since the early 20th century. This infrastructure hosts the digital memory of a small Athens-based community that prioritizes minimal data usage and privacy over the monopoly and centralization of big data centers and cloud services.

The digital data is stored within the DNA of the plant, making its survival entirely dependent on the plant’s life and behavior. On one of the most visited tourist sites in the world, the plant’s survival strategy hinges on invisibility, and the community is devoted to preserving its secret locations. Introducing and embracing this fragility is a core characteristic of this poetic work, as the survival of both ecosystems—human and plant—is rooted in interdependence and mutual care. The community has even developed a wordless, polyphonic chant as a protocol for communicating with the plants.

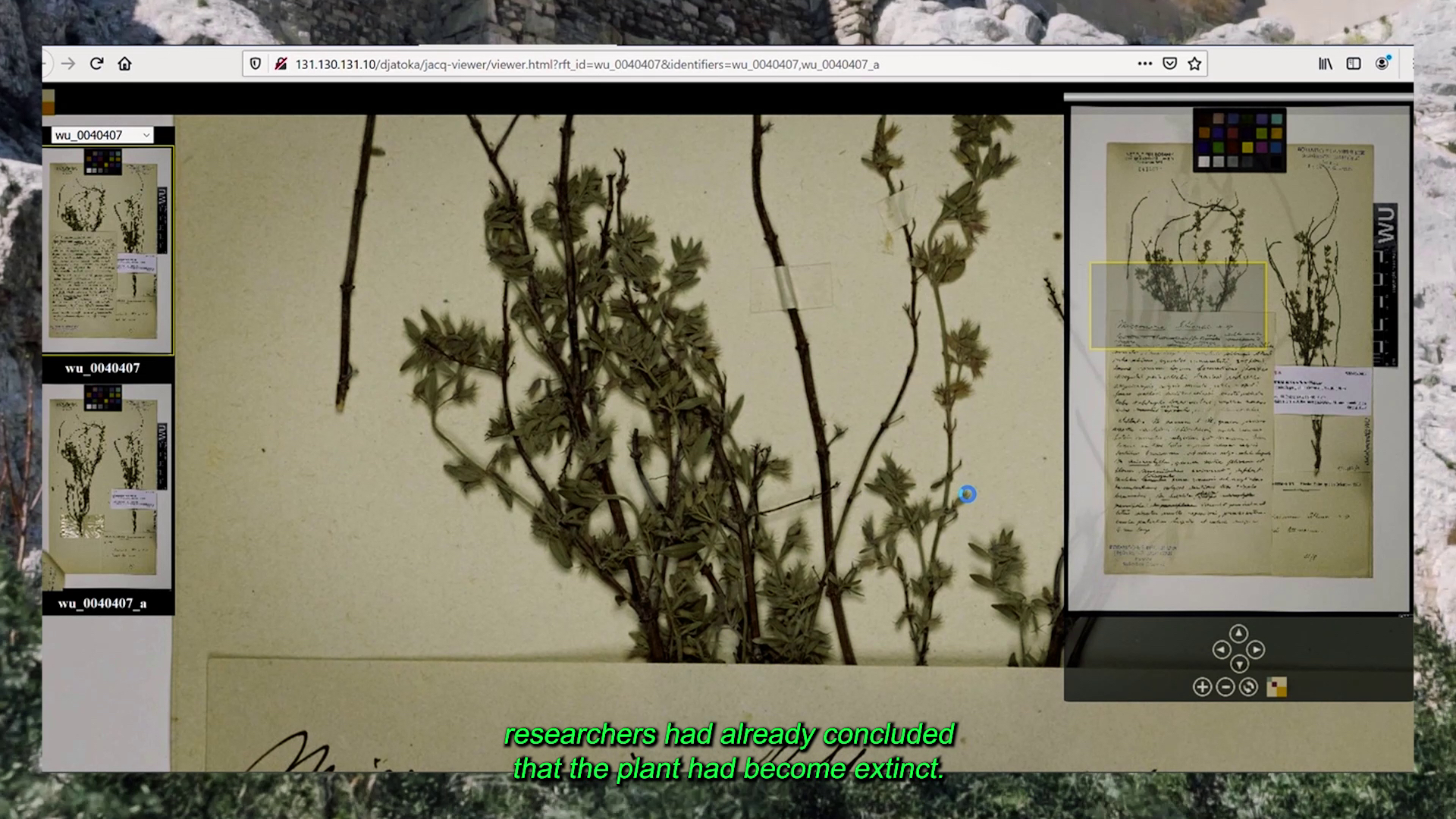

Image: A Way of Resisting (Athens Data Garden), video still 2020 ©Kyriaki Goni

While much of the project is fictional, its two main components are based on factual elements: the existence of the plant and the ability to store and retrieve digital data in organic DNA. The installation includes a video essay documenting encounters with the community, interviews with the botanist who rediscovered the plant in 2006, the biologist who successfully stored digital data in DNA in 2014, and other researchers. Among them is Mel Hogan, who discusses the potential and implications of introducing such an infrastructure as an alternative to today’s centralized systems.

Beyond its critique of the monopoly and control inherent in data centers, the work also highlights their materiality and immense energy requirements. Turning to plant DNA as an alternative reflects an urgent acknowledgment that current data center infrastructures are so energy-intensive and water-dependent that they are unsustainable in the long term. As mentioned earlier in this text, scholars like Mel Hogan have extensively studied the material and ecological impacts of digital infrastructures, providing critical context for this project.

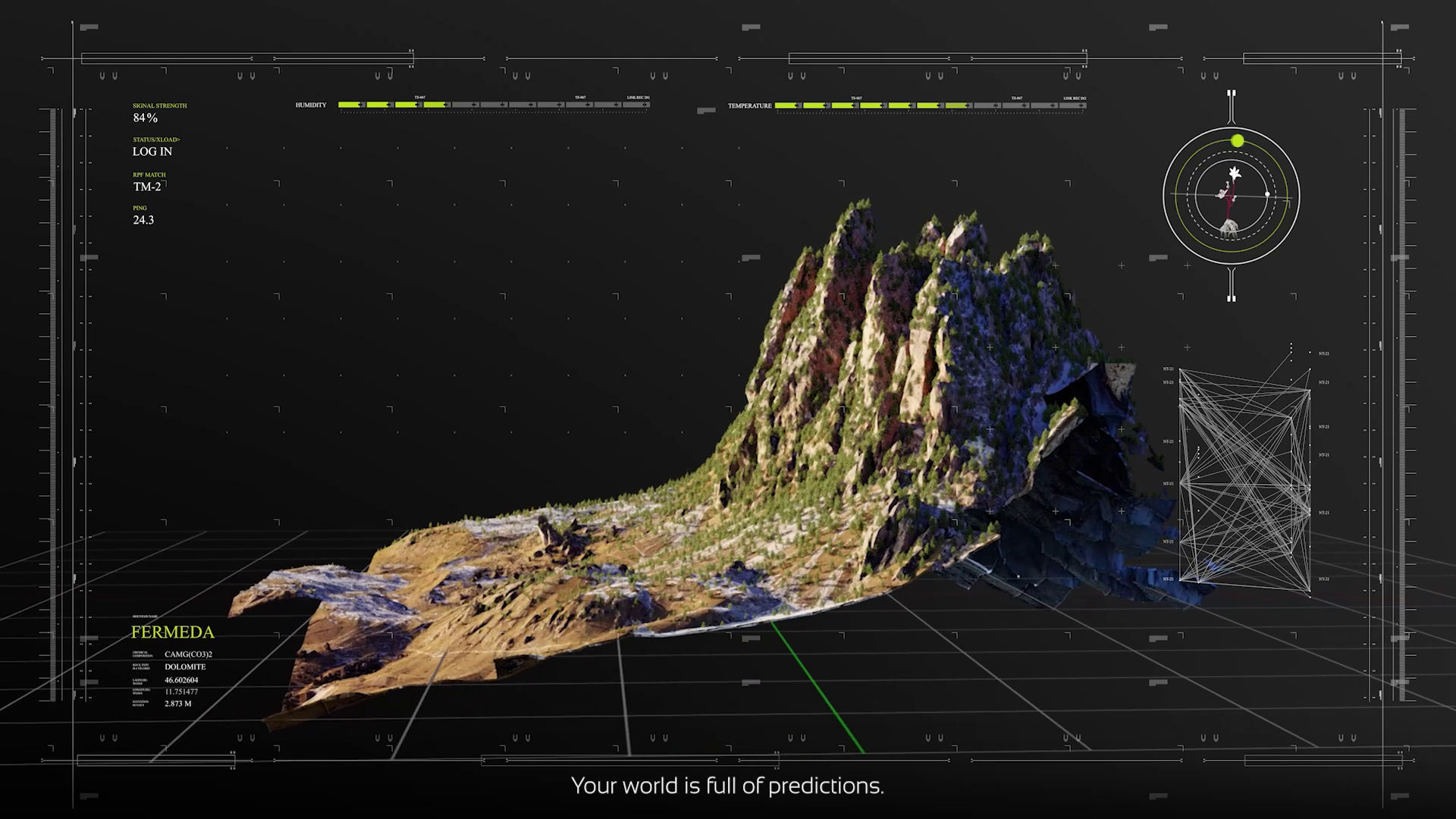

Indeed, climate change should force a reconfiguration of ecosystems and infrastructures, as poetically and urgently discussed in The Mountain Islands Shall Mourn Us Eternally (Dolomites Data Garden) (2022).11 The GCI video presents a simulation of the upward migration of tree species on a digital twin of the Fermeda mountain in the Dolomites, as they seek cooler climates. This phenomenon underscores that infrastructure is not only human-built but also encompasses the natural systems that support life. Just as trees adapt to survive, our infrastructure systems must evolve to accommodate the shifting realities of climate migration and species survival. The Mountain Islands Shall Mourn Us Eternally captures this ecological adaptation through a digital simulation of the Dolomites that spans from ancient epochs to a speculative future. The work explores how plant life has continuously responded to environmental changes, beginning in an era when the Dolomites formed a tropical archipelago, advancing through millennia of adaptation, and arriving at a speculative point where native plants migrate to higher elevations in response to rising temperatures. Here, a hybrid plant—combining characteristics from past and present species—emerges as a narrator, guiding viewers through the landscape’s transformation. This hybrid voice raises essential questions: How does a plant perceive its surroundings? What knowledge does it gain from environmental cues, and what role does this awareness play in its survival?

Image: The Mountain Islands Shall Mourn Us Eternally (Dolomites Data Garden) video still 2022 ©Kyriaki Goni

The hybrid plant, as narrator, invites us to consider the experience and agency of the non-human world. It poses a challenge: while humans have developed sophisticated climate models, have we truly listened to the lived experiences of other species? This work challenges our assumptions of dominion over nature and questions the efficacy of infrastructure that disregards the intelligence of non-human life. The hybrid narrator ultimately serves as a metaphor for a multispecies resilience, urging us to design infrastructures that are as sensitive and adaptive as the natural systems they inhabit, that are affective and allow for multiplicity.

Image: The Mountain Islands Shall Mourn Us Eternally (Dolomites Data Garden) video still 2022 ©Kyriaki Goni

Donna Haraway’s concept of ‘staying with the trouble’ and her work on ‘multispecies justice’12becomes crucial in both previously mentioned works. Haraway argues that we must embrace the complexity of living with other species, not merely as caretakers but as collaborators in a shared world. Her work calls for an infrastructural rethinking that recognizes the agency of non-human life and the interconnectedness of all beings. This ‘staying with the trouble’ is an ethic of care and responsibility that calls for infrastructure designs that engage with both human and non-human needs, recognizing the multi-dimensional aspects of survival and resilience in a changing world.

This work seeks to approach the way non-western knowledge systems offer valuable insights into infrastructure design that challenges the hierarchical and extractive models common in Western frameworks. Rooted in relationality, reciprocity, and respect for non-human agency, non-western cosmologies present infrastructure as a participatory, cyclical process that honors interconnectedness. This perspective regards rivers, forests, and mountains as kin, recognizing their agency within a larger web of life. These views remind us that infrastructure is not simply a human tool; it is a network of relationships with multiple agents.

Image: The Future Light Cone 2022 ©Kyriaki-Goni. INDEX-Biennale Portugal 2024. Photo by Adriano Ferreira Borges

Transitioning from the realms of water and soil on our planet to the vast expanse of space, I would like to conclude this text by introducing another multimedia installation that explores the concept of infrastructures. The Future Light Cone (2022)13 constitutes of six tapestries, a video, drawings and a tungsten cube. This series of tapestries the Martian landscapes features landscapes selected from NASA’s image collection. These woven surfaces bring the landscapes into focus with striking materiality, inviting reflection on how documentation and the act of bearing witness could shape our responsibilities toward other worlds.

The tapestries follow traditional practices by incorporating decorative bordures with colorful motifs. They combine images of technological tools—such as calibrators, fiber optic cables, and spaceships—with historical references to colonialism and technological advancement, including the coiling of transatlantic cables and the notion of “the conquering of the West.” Short texts from the broader discourse on space exploration appear on the upper sections of the tapestries. Serving multiple purposes, the tapestries evoke their historical roles as sails, packable shelters, and warming decorations, symbolizing human movement and settlement across centuries. Simultaneously, they represent a medium for sharing knowledge and stories through the act of weaving itself.

Image: The Future Light Cone 2022 ©Kyriaki-Goni. INDEX-Biennale Portugal 2024. Photo by Adriano Ferreira Borges

In the video Signal from Mars, Perseverance Rover landed on Mars on February 18, 2021, enhanced by cutting-edge artificial intelligence, detects signals that are both unfamiliar and enigmatic. The audio transitions to the soundscape of Mars: the eerie whisper of the Martian wind, and a nonhuman message seems to defy explanation. The video pans across the desolate landscape—the jagged rocks, vast dunes, and the faint outlines of what could once have been riverbeds. Subtle visual distortions suggest the signals are emanating from something unseen, buried deep within the planet’s crust. The mysterious transmission originating from the weathered rocks, ancient minerals, or the remnants of a primordial ocean hidden beneath the dusty red exterior includes questions about the motivation of Mars’ exploration, the possibility of coexisting among other things.

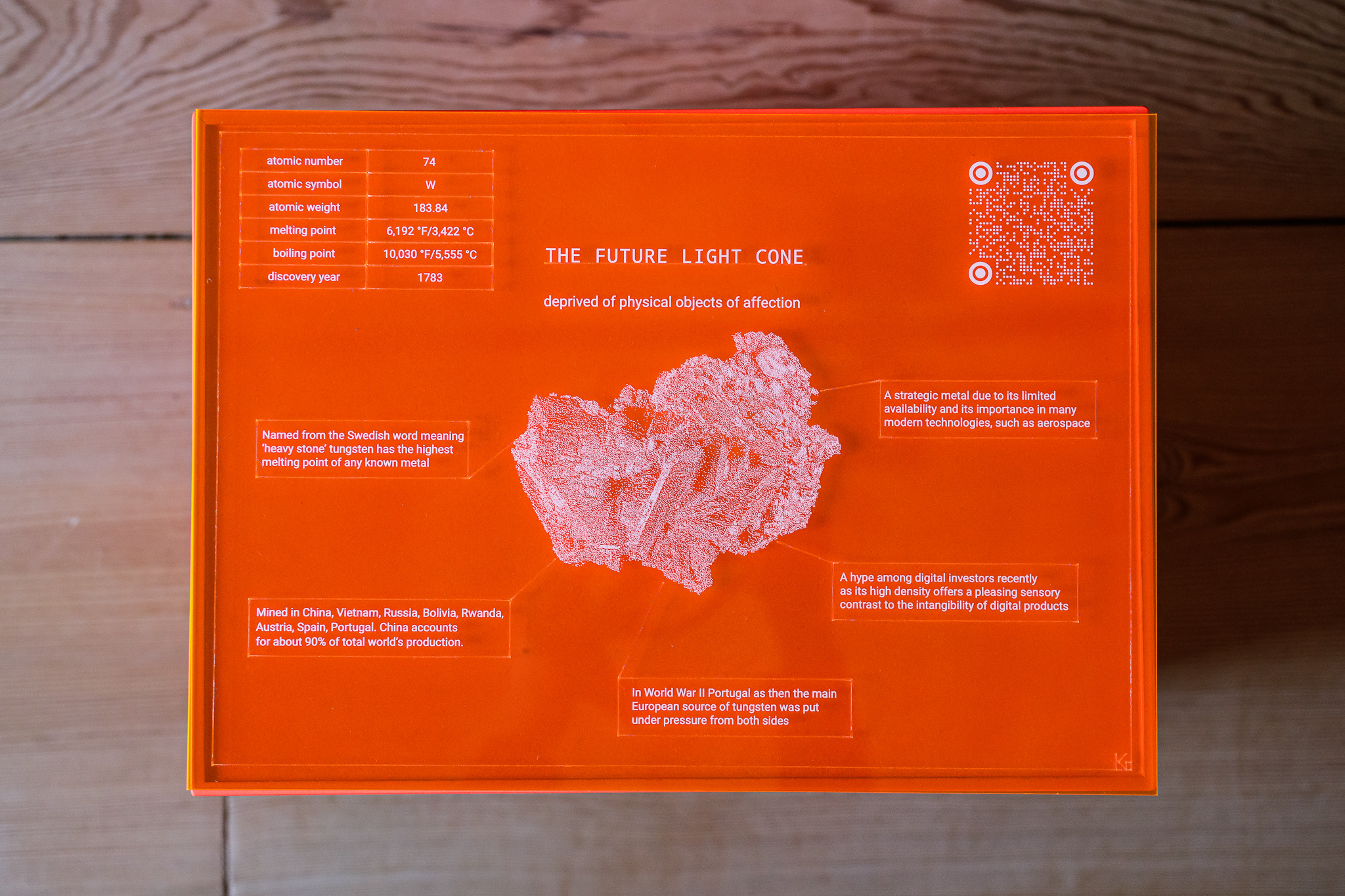

Touching again upon materiality of infrastructures, with the title Deprived of Physical Objects of Affection, the Wolfram (W), more commonly known as Tungsten cube included in the installation, derives its name from the Swedish term for “heavy stone.” Recognized as one of the densest elements on the periodic table, tungsten has a remarkable range of industrial applications, including its use in paneling for nuclear fusion reactors, rocket engine nozzles, and other high-performance technologies. Its extraction history dates back to 16th-century Germany, with the Nanling Mountains in southern China now hosting approximately half of the world’s known tungsten deposits, underscoring its geopolitical and economic importance.

Image: The Future Light Cone 2022 ©Kyriaki-Goni. INDEX-Biennale Portugal 2024. Photo by Adriano Ferreira Borges

The cube’s extraordinary density offers a unique tactile experience, creating a striking contrast with the intangibility of digital currencies and virtual products—a feature that has fueled its popularity among digital investors. In this context, the cube serves as both a representation of its “dense” materiality and as a commentary on the broader implications of extractivist practices, drawing attention to the physical and environmental costs embedded in technological progress.

The installation also comprises a series of 12 drawing notes, Notes of Space Exploration, where the space exploration is thoroughly visited as an idea, as a system of infrastructures and a possible future, raising questions on the further development of these.

The Future Light Cone (2022) examines the discourse surrounding space exploration, particularly since 2016, as shaped by Silicon Valley’s colonialist narratives. These narratives often position space as an extension of human conquest, reinforcing anthropocentric ideologies that prioritize human agency over other forms of existence. However, this framing is increasingly critiqued, prompting questions about whether an anti-colonial language can emerge to shift away from the extraction-driven mentality dominating current discussions. Feminist perspectives offer a potential avenue for rethinking space exploration, centering care, relationality, and the recognition of other-than-human agencies.

Contrasting the traditional view of space as a frontier for human expansion, the installation proposes an alternative perspective. Other worlds are not presented as blank slates to be terraformed and exploited but as agents with inherent knowledge systems. This vision challenges entrenched anthropocentric narratives, encouraging a broader recognition of diverse cosmologies beyond the human. Simultaneously, the rise of longtermism—promoted by tech giants advocating for space colonization as a solution to Earth’s existential crises—aligns with corporate-led space economies. These developments prompt critical questions about the emerging political ideologies of space, including their intersections with authoritarianism and corporate control over planetary futures.

The current global landscape’s shift toward right-wing populism and authoritarianism has profound implications for infrastructure. Nationalist ideologies seek to centralize power and suppress dissent, while corporate visions of interplanetary expansion, exemplified by SpaceX and the U.S. “Space Force,” project these authoritarian tendencies onto space. This corporatist and nationalist interplanetary order envisions space not as a site of coexistence but as a frontier for domination, accessible only to an elite few. Such a vision exacerbates infrastructural inequality, leaving marginalized populations on Earth to confront escalating climate risks while the privileged retreat to “off-world” futures.

The installation engages deeply with planetary infrastructures, critiquing the physical and ideological systems—rockets, factories, launching areas, satellites, data networks—underpinning space exploration and their entanglement with corporate and nationalist agendas. These infrastructures reflect the same extractive and colonialist practices shaping terrestrial systems, underscoring the interconnectedness of planetary and interplanetary futures.

The Future Light Cone calls for a reimagination of these infrastructures, advocating for systems that are collaborative, relational, and ecologically responsible. Feminist critiques inform this vision, emphasizing care, the recognition of non-human agency, and ecological justice. By critiquing longtermism, the work highlights how such ideologies shape space infrastructures that often neglect justice and equity in favor of corporate and nationalist priorities.

Ultimately, the artwork ties space exploration to broader considerations of planetary infrastructures on Earth. It suggests that how humanity builds and manages its systems—whether for domination or coexistence—reflects ideological frameworks shaping the future. Through its critique and alternative vision, The Future Light Cone underscores the necessity of viewing infrastructures as tools for resilience, equity, and global collaboration, both on Earth and beyond.

In conclusion, the future of infrastructure must be seen as a practice of care—an evolving network of relationships that respects the interdependence of all life forms. This vision requires a radical rethinking of power structures, prioritizing decentralized, cooperative, and relational systems. By rejecting the top-down models of corporate control and authoritarianism, infrastructures need to promote justice, ecological sustainability, and inclusivity. These infrastructures will be defined not by efficiency but by trust, care, and connectivity, ensuring that the futures built are not only sustainable but equitable and imaginative, rooted in a shared commitment to planetary well-being. Of great importance here is how different POVs can do the design of the infrastructures and radically form them, how they to take into account different cosmologies and needs. Art and world-building have provided me with the opportunity and space to envision alternative infrastructures and, most importantly, to foster and sustain a dialogue with a broader audience on these topics.

Kyriaki Goni is an Athens born and based artist. Working across disciplines and technologies, she creates expanded, multi-layered installations. She connects the local with the global by critically touching on questions of technology, more specifically on surveillance, distributed networks and infrastructures, ecosystems, human and other than human relations. Her work gets exhibited worldwide in solo and group shows. Recent solo shows were presented at Onassis Cultural Centre, Athens; Aksioma, Ljibjana; Drugo More, Rijeka. Recent group exhibitions include Ars Electronica, 13th Shanghai Biennale, Transmediale2020, 5th Istanbul Design Biennial, Glass Room San Francisco, Melbourne Triennial, etc). She is a Delfina Foundation alumna (2019), and she has received fellowships such as Allianz Kulturstiftung (2021), Niarchos Artworks fellow (2018), etc. Her latest work Data Garden received the Greek state prize INSPIRE2020. Her works are part of private and corporate collections. She is a graduate of the Athens School of Fine Arts with an MA in Digital Arts, before which she had pursued a BA and an MSc in Cultural Anthropology and Developmental Sociology from Leiden University. Further info at kyriakigoni.com